In this 13th year of my production, for public radio, I present the narrative and play list to “Las Cantigas de Santa Maria: A Musical Biography of 13th Century Monarch, King Alfonso X”

I dedicate this program to my mentor, the late David W. Bauguess and to all music teachers who instill the love of music in their students.

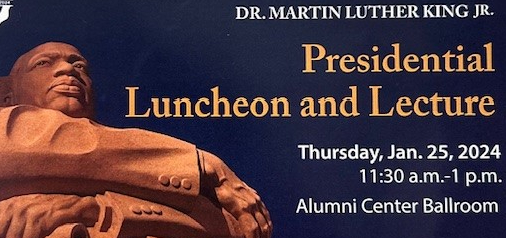

I invite you to listen to this program on December 24, from 2:00 to 4 p.m. in the Central Time Zone. The public radio station that has sponsored Las Cantigas in this 13th year is High Plains Public Radio. Please tune in on hppr.org under holiday programming (not to be confused with HPPR connect, the talk show portion of their dual programming).

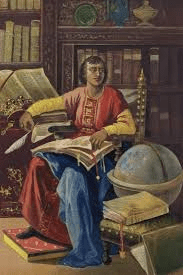

Hello. I’m Debra Bolton. Welcome to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria (The Holy Canticles of St. Mary), Songs and poems in praise of the Virgin Mary – and the poetic/musical biography of Alfonso, “the wise”, The King of Castile-Leon, now Spain, and who lived from 1221 to 1284. I’m happy you’ve joined me today.

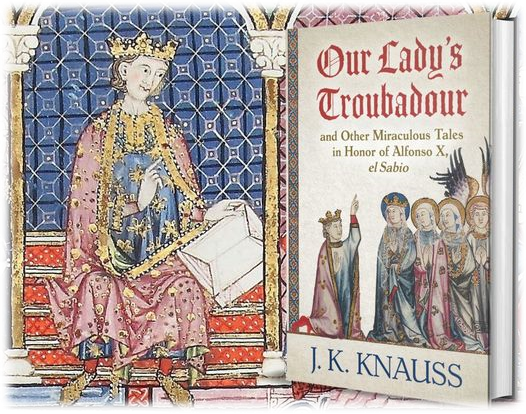

Today, my research comes from the authors Deirdre Jackson, Dr. Jessica Knauss, and Emilio Villalba with Sara Marina, and Maestro Jordi Savall.

I like to begin this musical journey with The Learned King declaring himself Mary’s Troubadour who will take her teachings to his Kingdom and beyond. We hear the prologue where The Learned King states, “I am here to spread your good word to my people, and in doing that, I pray for my place in the Kingdom of Heaven.”

This is Pavel Zarukin 1:18

Followed by the spoken declaration that Alfonso the Wise states that from henceforth, he will be Mary’s troubadour. :18 and CSM #4 by Ricardo Alves Pereira with the Prologue CSM B 3:47

That was Ricardo Alves Pereira with an instrumental version of the CSM Prologue B and King Alfonso X announcement that he serves as the Virgin Mary’s troubadour, henceforth, from Emsemble Obsidienne with Emmanuel Bonnardot. the Learned King’s spoken declaration that he is Mary’s greatest public relations ad man, so to speak. Alfonso pledges to use every means to extol Mary’s virtues, especially where her miracles are concerned.

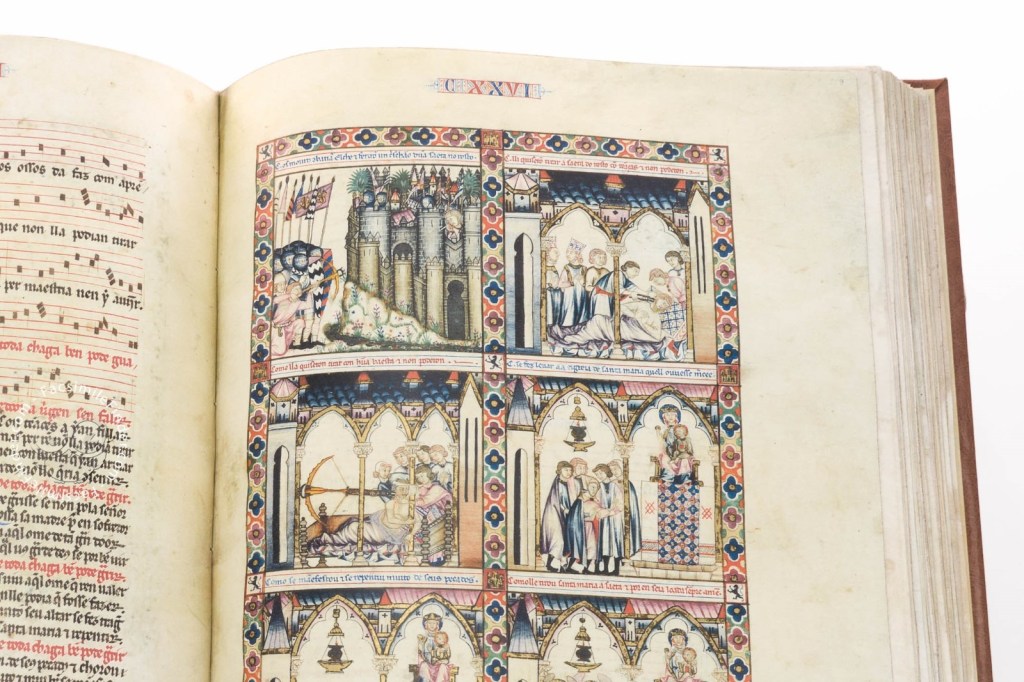

In writing about the Enigma of the Cantigas de Santa Maria or the CSM, Emilio Villalba, says, “The curious thing about this marvellous musical monument from the 13th century is that it still holds many secrets and enigmas that make this work even more valuable.” He adds, “There is no doubt that Alfonso was one of the first kings to sign a musical book, making this work a unique codex.

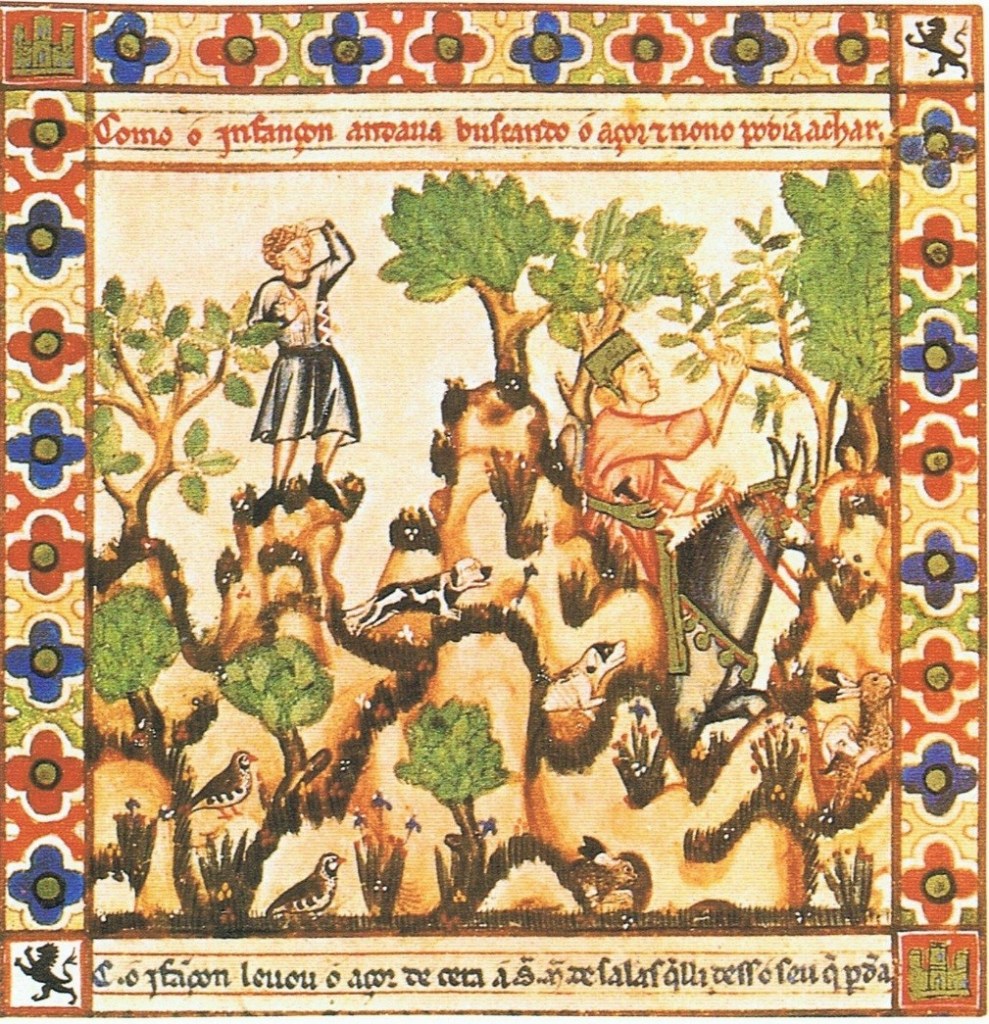

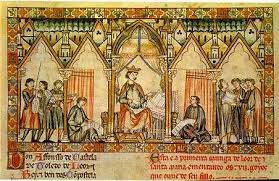

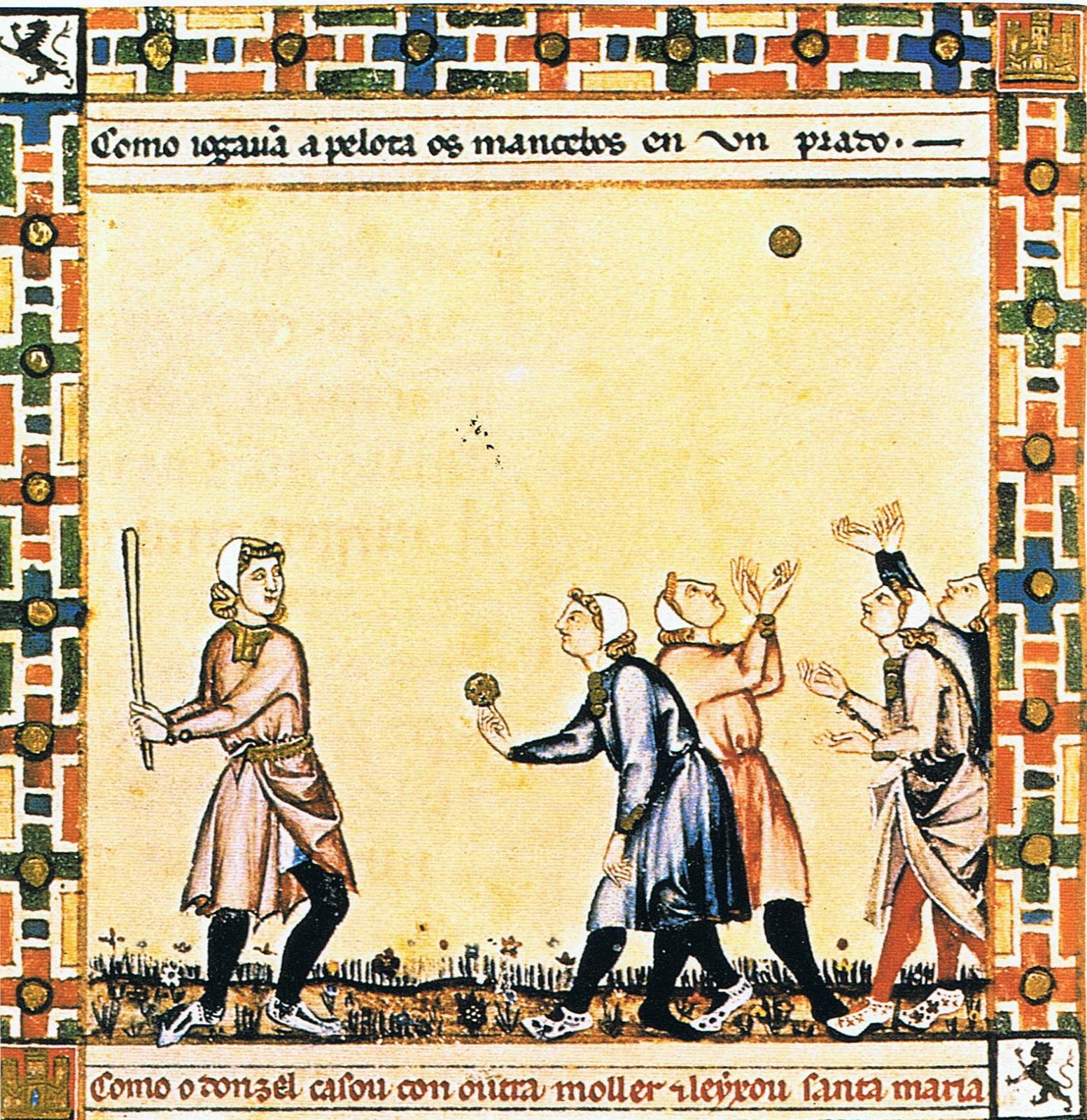

The CSM collection consists of poems put to music. The king also engaged 2D and 3D artists to depict visually what the songs portrayed. The catalog consists of more than 420 poems set to music beginning with what is called a “cantiga de loor” song of love, that is “courtly love” and every 10th song is a song of love while the others focus on scenarios related to sins and crimes with their accompanying stories of Mary’s miracles from which Alfonso X hopes to promote morality in his kingdoms of Castile and Leon, which later become what we know as Spain.

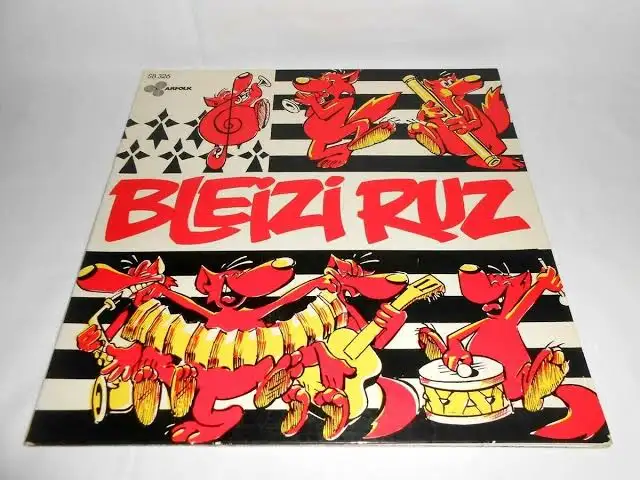

Let’s turn to the works of This Breton band called Bleizi Ruz, meaning red wolves in the Breton language. This interpretation demonstrates that the Cantigas de Santa Maria continues to be of interest to musicians and scholars world wide. Here Blizi Ruz collaborates with Spanish Ensemble, La Musigaña.

Cantigas de Santa Maria: 4:04

CSM 1 – Des oge mais quer’ eu trobar. Hana Blaziková, Barbora Kabátková, Margit Übellacker & Martin Novák 5:44

That was Hana Blaziková, Barbora Kabátková, Margit Übellacker & Martin Novák performing CSM 1, The Seven Joys. We began the set with Blizi Ruz and La Musigaña with an instrumental of CSM 1.

You can find this transcript, along with photos, and links in my blog, Peopleandcultures.blog. Look for “Cantigas de Santa Maria 2025”

You’re listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, a musical biography of Medieval King Alfonso X and his devotion to the Virgin Mary. In this, we come to understand the miracles of the Virgin Mary as seen through the eyes and ears of Alfonso X, who ruled what is now Spain during the 13th Century.

Each year, when I prepare this production, I like to read different scholarly interpretations of the CSM. King Alfonso X remains an enigma. Instead of having his musicians and scholars do the work, he worked alongside them offering his own poetry and musical notations to the songs praising the miracles of the Virgin Mary. Musician and musicologist, Emilio Villalba posits that four copies of the vast works were made so that the King could have them at each of his palaces. During great illness, the King held the rather weighty volumes on his chest as a sort of balm for healing.

We’ll dive into works of other Alfonsine scholars later in this program. Let’s continue with an Arabic tribute to the Virgin Mary. Remember, King Alfonso X was a pluralist, and he ruled his kingdom, rather effectively, with Muslims, Jewish, and Christians side by side. We’ll hear two version of a la quarte estampie royal. A Royal dance, specifically of Medieval times:

La quarte estampie royal – Ensemble Alcatraz 2:33

La quarte Estampie Royal – Jordi Savall 4:47

We just heard Jordi Saval and his Hesperion XXI (21) from an album called Estampies & Danses Royales on the Alia Vox label.

You’re listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, a musical biography of Medieval King Alfonso X. I’m Debra Bolton. We now pause for this station break: 2:00

Welcome back to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, a musical biography of 13th Century monarch, King Alfonso X, who ruled what is now Spain from 1251 to 1284. I’m your host, Debra Bolton. A friend from Spain shares a few articles he’s found on King Alfonso. One such article, Work and Workers in Alfonso X’s CSM by Deirdre Jackson, sheds light on ways men and women coped with work challenges from work accidents to crop failure. Some scholars posit that Alfonso the Wise made a conscious effort to preserve ways of life in his kingdom, while committing himself to creating a cultural time capsule in the dominant language of the time: Galician-Portuguese, the embryonic Castilian of today. We’ll hear two pieces of the CSM that speak to work life, with the added twist of Mary intervening to ease a tragedy.

CSM 213 tells the story of A man named don Tomé from Elvas who made his living carrying things to market on his beasts. Tome worked with the thought that his wife was faithful to him, but he was mistaken.

One day authorities found her stabbed to death. When Tome returned to Elvas, they tried to arrest him, but he fled to the border.

He settled in Badajoz, and decided to go to Terena on pilgrimage hoping the Virgin would protect him from arrest, since the charge was unjust. He prayed to the Virgin to have mercy on him and to defend him.

On his return to Badajoz, he encountered his enemies, but the Virgin prevented them from seeing him. Still hoping to find him, they went to Terena. On a riverbank, they saw the devil in the man’s guise.

Once the devil’s trick was revealed, the authorities understood that Tome was innocent, and they begged his pardon.

Here we have Tomoko Sugawara, performing CSM 213 on the Konghou, a plucked concert harp instrument of ancient China.

CSM 213 Tomoko Sugawara 3:49

CSM 267 Aquel Trovar 4:44

That was Aquel Trovar performing CSM 267, A rich merchant from Portugal vowed someday to go on pilgrimage to Rocamadour.

The merchant loaded his ship and sailed up the Atlantic coast toward Flanders. The ship was struck by a storm and the merchant was thrown into the sea. As he sank into the waves, he asked the Virgin to save him. The Virgin calmed the sea and carried the merchant to dry land.

The ancient city of Rocamadour, with a current population of 604 people, includes buildings that appear to have been carved in the clifftop. Considered a religious city in the Occitania region of southern France, Rocamadour borders Spain and features the body of St. Amadour and the sculpture of the Black Virgin. This village figures into the CSM frequently.

Let’s hear CSM #8, the Minstrel of Rocamadour, named, Pedro de Sigrar, who sang and played his fiddle in front of a statue of the Virgin. He prayed that she’d give him a candle, and she caused one to rest on his fiddle. A monk, the shrine treasurer, snatched it back, and accused the minstrel of sorcery. The candle returned to the fiddle and the people, seeing this, did not allow the monk to take it away from the minstrel again. The monk acknowledged the miracle, repented, and asked the minstrel’s pardon. This is the Waverly Consort with the late Michael Jaffee, leading.

CSM 8: A virgen Santa Maria Pt. 1 0:19

CSM 8: Song 3:38

That was the Waverly Consort from their album: Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, one of my first encounters with the CSM, and it continues to delight.

You’re listening to a musical biography of Medieval King Alfonso X of what is now Spain. I’m your host Debra Bolton. Thank you for listening. Coming up in the second hour of Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, we’ll look at some contemporary interpretations of the CSM, including electric guitars replacing instruments of the 13th Century.

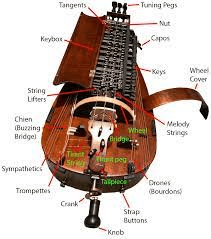

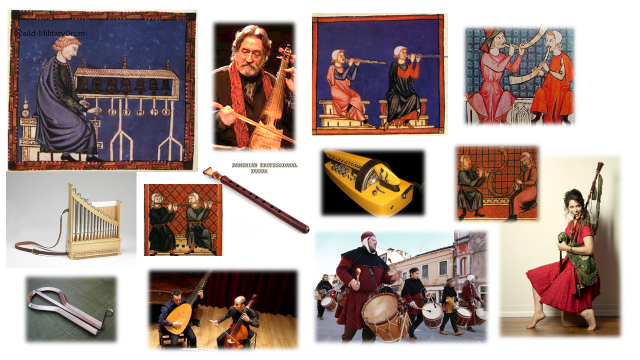

In this vast collections of the CSM, we learn that of the 420 songs, every 10th song is a Cantiga de Loor, a song of courtly love. Let’s continue with Maestro Eduardo Paniagua, a musicologist and multi-instrumentalist specializing in period instruments of the time including viola de rueda, a.k.a. the hurdy gurdy, the oud (precursor to the guitar), the organetto (a portable organ), and varying horns and recorders. You can see some of these instruments on my blog: peopleandcultures.blog. We’ll hear CSM 80 and CSM 130, songs of courtly love, performed by Eduardo Paniagua.

CSM 80 2:54

CSM 130 3:02

We just heard Eduardo Paniagua with CSM 80 and 130, songs of courtly love.

As we approach the top of the hour, I hope you join us for the second hour to further our exploration of the history, the music, the King’s goals for this vast collection, and much more.

Let’s listen to Frederic Hand performing, what he calls, a CSM fantasy followed by CSM 139, the boy who offered bread to the Christ Child. You’re listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, a musical biography of Medieval King Alfonso X. I”m your host, Debra Bolton.

HR 1 Segment 2 total timing: 29:27

HR 2 Segment 1

Welcome to the second and final hour of this holiday special Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, the holy canticles of the Virgin Mary and musical biography of Alfonso X, the King of Castile-Leon, now Spain. I’m your host, Debra Bolton.

Alfonso X ruled from 1252 to 1284. To put the world into perspective at the time, the English language continued to change from its Germanic-rooted Olde English of the Beowulf poet (circa 9th or 10th century) after the Norman invasion of 1066. In the next century, we hear the English of Geoffrey Chaucer of Canterbury Tales fame and the Gawain Poet. Europeans now use Arabic numerals in favor of Roman Numerals. In the Mongol Empire, Mongke, officially, marks the worship of his grandfather, Genghis Khan while Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity flourish. The Inca Empire of Peru is thriving. England begins the process of segregation of Jewish peoples, and other countries begin to follow suit. Poland became a place of refuge for exiled and homeless Jewish Peoples, but it later became host to many Jewish death camps under the Hitler regime. The Mexica people, also known as Aztecs, are building their great capital city Tenochtitlan on Lake Texcoco, what is now Mexico City. King Alfonso X’s bid to be King of the Holy Roman Empire but fails as Pope Alexander IV (4th) denies Alfonso’s rights to the throne in favor of Count Rudolf, bringing prominence to the Habsburg family. Count Rudolf was considered mediocre by many, as Alfonso was too ambitious and certainly too bright for that particular Pope of the time.

From the 13th to the 21st Century, the Cantigas de Santa Maria continue to influence new and exciting interpretations. Let’s begin this second hour looking at an electric influence of one of the most recognizable of the CSM, , and since it has an even number, 100, we know that it’s a song of love. Here we have Gabriel Fox with his contemporary interpretation of CSM 100.

Gabriel Fox, CSM 100 2:37

Takashi Tsunoda, CSM Medley 6:26

That was Takashi Tsunoda performing on the Oud Harp, an instrument that he helped to build. Tsunoda also plays the gourd banjo in that piece. Tsunoda is listed under classical, jazz, and world music genres.

You’re listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria. I’m Debra Bolton, your host. By the bye, you can read the transcript along with photos of the instruments and the musical playlist on my blog, peopleandcultures.blog. Also, you can comment or communicate with me through the blog, too.

Let’s continue with our exploration of the CSM. Often, the performers will list their song or instrumental by the first few lines of the poem. Thanks to the Oxford Cantigas de Santa Maria database, I can find the CSM number by using the lines from the poem. Let’s hear Enea Sorini’s interpretation of CSM 48, the stream that was diverted for the monks of Montserrat.

CSM 48 3:46

CSM 77-119 by Forfaitz 5:12

That was the Ensemble Forfaitz with CSM 77-119. I can find little to no information about Ensemble Forfaitz other than they play with Ensemble Unicorn. I’ve noticed that many interpreters of the CSM tend to bundle CSM 77-119 into a medley. Rather than my telling you what each of the stories entail, this is where you can find each of the 420 poems: the Oxford Cantigas de Santa Maria database. I continue to be fascinated by the stories in each of the poems.

King Alfonso ruled Castile-Leon in the Iberian Peninsula. If you think about it, Muslim rule began in 711 and lasted until 1492, the year of the Inquisition, when Muslims and Jewish people were victims displacement by Christian rule some 200 years after King Alfonso X’s rule. Alfonso the Wise ruled alongside his Muslim counterparts.

Let’s listen to the music of al-Andalus, the name of Muslim rule of the region. This is Eduardo Paniagua, an architect, musicologist, and multi-instrumentalist dedicated to reviving the music of the Iberian Peninsula in the Medieval era. Here he plays with Ensemble El Arabi. This is called Cordoba Lozana

El Arabi with Eduardo Paniagua Cordoba Lozana 5:52

That was El Arabi with Eduardo Paniagua. You’re listening the a musical biography of Medieval King Alfonso X, Las Cantigas de Santa Maria. I’m your host, Debra Bolton. Let’s take this break from your public radio station, and then we will return with the second part of this hour.

Music bed: Istampitta: La Manfredina (Italia Medieval) Jordi Savall 2:00

(Hour 2: Segment 2)

Welcome back to the final segment of Las Cantigas de Santa Maria. I’m your host, Debra Bolton Thank you for listening and for supporting your public radio station.

Scholars and Alfonsine devotees continue to celebrate the Learned King’s birthday on November 23 of each year, this being the 804th year since his birth in 1221.

Let’s discuss, for a moment, the language of King Alfonso X.

In a past interview with Alfonsine scholar, Dr. J. K. Knauss, she noted that the great legacy of El Sabio is that he lived up to his name, “the wise” because he was obsessed with writing everything down. Whether it was mathematics, astronomy, the virtue of playing board games and other leisurely activities to balance hard works, laws to govern his subjects, and teaching morality, he not only wrote continually, but he chose not to write in Latin, the language of Kingdoms of the day. What made his legacy so strong is that he wrote in Galician-Portuguese, the embryonic Castilian, the present-day Spanish, though, like all language, changes continually as it incorporates varying native language of the Americas and other places colonized by Spain . The Learned King is considered the “Father of Castilian.” Was he that much of a visionary? It would seem so since Spanish only trails Chinese as the most common language worldwide, flanked by English, Arabic, Hindi, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, Japanese, and Lahnda, aka, “Western Punjabi” according to The World Economic Forum and Encyclopedia Britannica online.

Let’s begin this segment with Maestro Jordi Savall, the music scholar, historian, and viola de gambist extraordinaire! I’ve had the great honor of attending three of his performances in Kansas City. Nearing 90, Savall still gathers musicians from around the globe to see his vision of bringing to the fore music through the centuries from composers, obscure and famous.

Here, we have Savall’s arrangement of CSM 248-353.

Ductia (CSM 248-353) ( 3:43) Jordi Savall

Je vivroie liement (I’ve been living)– Ensemble Gilles Binchois 3:06

You’re listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, a musical biography of King Alfonso X, I’m Debra Bolton. That was Ensemble Gilles Binchois with Je vivroie Liement, I’’ve been living! Preceded by Jordi Savall with his arrangement of CSM 248-353.

When I spoke to Alfonsine scholar Dr. J.K. Knauss, who lives in Spain and focuses on writing books, non-fiction and historical fiction, she told me that the higher the number in the CSM collection of more than 420 poems, the more local the miracle is happening.

Let’s hear Hana Blažíková performing CSM 383, The Pilgram woman saved from drowning, saved by the Virgin to whom the woman prayed.

CSM 383 – Hana Blažíková O fondo do mar tan 5:07

Alfonso X El Sabio – Narciso Yepes 4:58

That was the great Narciso Yepes, born in Lorca Spain in 1927 and died in Murcia, Spain in 1997. Yepes brought to prominence, the 10-String Classical guitar known for its range and timbre. Yepes performed his arrangement of a CSM medley in 1989.

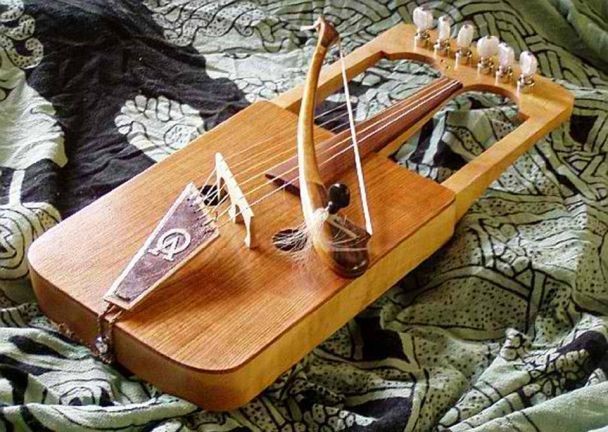

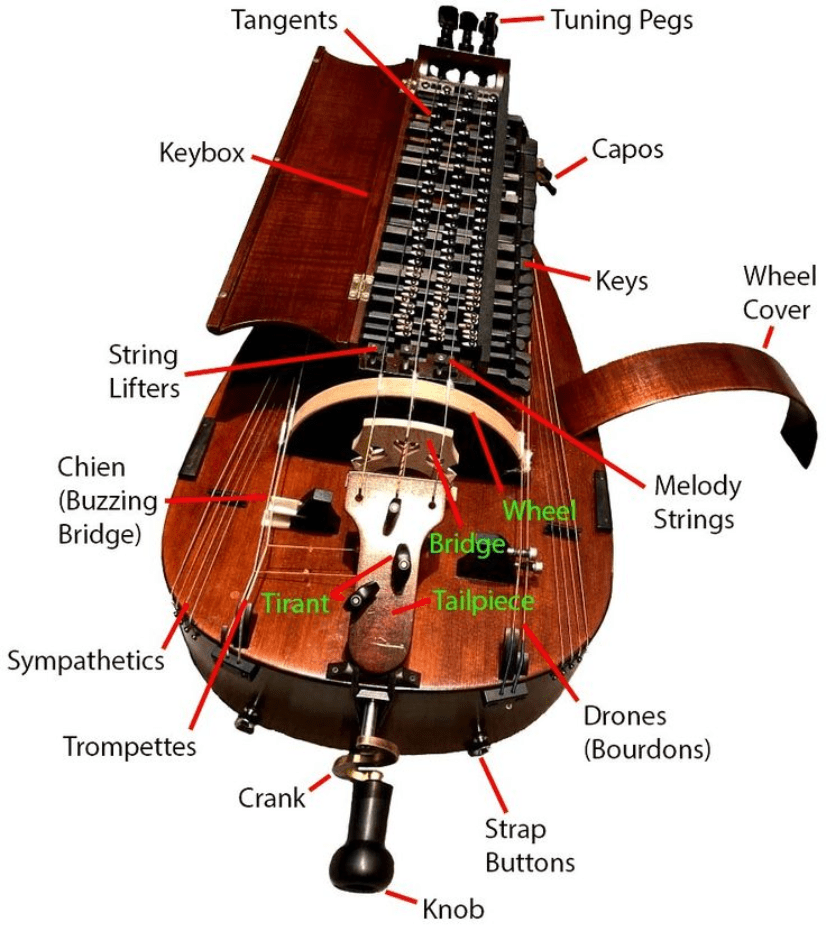

Well, our time together is waning. Thank you for listening to this special programming, Las Cantigas de Santa Maria with your host, Debra Bolton. Be sure to check out my blog, peopleandcultures.blog for this narrative and song selections. You can also see pictures of the medieval instruments featured on this show. Speaking of instruments, let’s hear the Viola de Rueda, which translates to a violin of the wheel. I’m speaking of the hurdy gurdy also called Zamphona. I read that it takes five years to build one hurdy gurdy. On my blog, peopleandcultures.blog I show the anatomy of the hurdy gurdy, a most fascinating instrument still played today. Let’s listen to Eduardo Paniagua and his Fuego de San Marcial.

Fuego de San Marcial Eduardo Paniagua 2:38

That was Musica Antigua led by Maestro Paniagua.

Thank you for listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria. I’m your host Debra Bolton. Thank you for supporting your public radio station.

To take us to the top of the hour, Waverly Consorts CSM medley Instrumental from Waverly Consort’s Las Cantigas de Santa Maria (6:43)

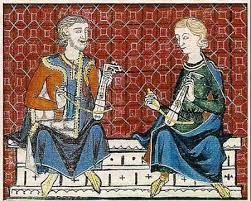

Instruments of the time:

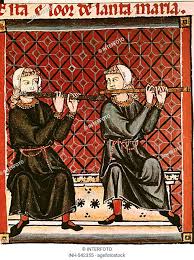

Shawm – 12th c conical bored double reed instrument of Middle Eastern origin, a precursor of the oboe. Like the oboe, it is conically bored; but its bore, bell, and finger holes are wider, and it has a wooden disk (called a pirouette, on European shawms) that supports the lips

Recorder – Yes. That woodwind instrument that many of us learned in grade school. We hear this in the CSM, usually, on a wider variety of wood recorders.

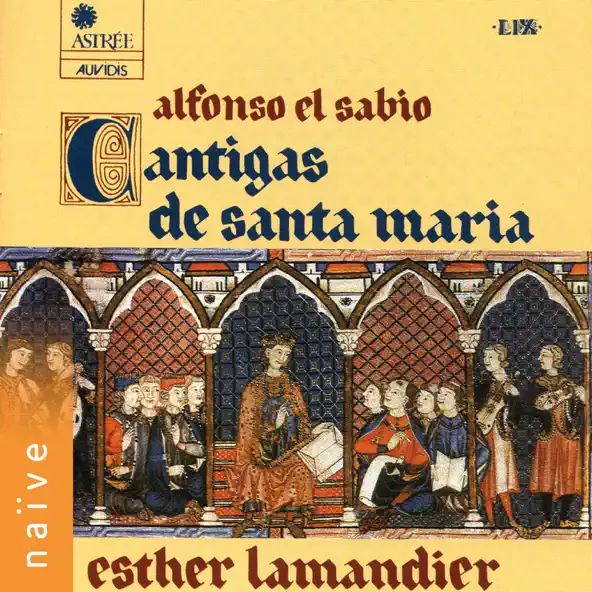

Organetto – a small portable organ, often championed by Soprano, Esther Lamandier

Oud – Literally, wood in Arabic, short-necked, pear-shaped with 11 – 13 strings grouped in 5, 6, or 7 courses. A few of the oud players that stand oud are Driss El Maloumi, a group called 3MA and Haik Egitim Merkezi Yalova, both Maloumi and Yalova perform with Jordi Savall’s Hesperion groups. The Oud is considered the most important instrument in Middle Eastern Music.

Qanun (a.k.a., kanun, ganoun, kanoon) an Arabic stringed instrument, introduced to Europe in the 12th Century. It’s played on the lap with picks that surround both index fingers, and the player can change the pitch of the strings with brass levers.

Hakan Güngör plays Kanun on the right, with Jordi Savall playing his vièle

Hurdy Gurdy, a.k.a. Viola de Rueda, and the Zanfona. Here we hear this instrument in Musica Antigua.

Vielle – the Medieval fiddle with five strings and six tied frets.

See image above

Rebec – A three-string “fiddle” often held between the legs as it’s played.

Viola de Gamba – (a.k.a., Viol or gamba), a six-stringed instrument, said to be a precursor of the four-stringed cello. The Gamba, usually, is much larger and has frets, like a guitar.

Gaita – Galician bag pipe, also common in Portugal.

Duduk – Double reed Armenian flute, featuring those mournful, lamenting tones. Haïg Sarikouyoumdjian, pictured below, plays with Jordi Savall’s Hesperion group.

I wrote this part for narrative, but did not include in radio program.

For perspective of the time, King Henry III ruled England about the same time Alfonso X ruled Castile-Leon, the greater part of what is now known as Spain. While El Sabio ruled his lands with Christians, Muslims, and Jewish peoples living and studying side-by-side with some appreciation and great tolerance, it would not be until 208 years later that Isabella and Ferdinand would expel all non-Christians and the time Christopher Columbus would set sail for Asia but landed in the Americas, which changed extensively the lives that he touched. Before that, well-civilized Indigenous tribes had not yet had contact with European colonizers. The surnames that most people connect with Latin American countries were the surnames of their Spanish conquerors. During and after the inquisition, many non-Christians, Jewish and Muslim people, added the suffixes of –ez, -es, or –os, meaning “son of,” to their surnames. For example, the Muslim man, Alvar, became Alvarez. The Jewish man, Martin became Martinez. Consistent with most surnames, there remained a connection to the family trade or place of origins. The Herrera were Sehphardic Jewish iron-smiths of Galicia. Those hailing from Galicia, or Galego, were the Galegos. In the present day, an extra “L” was added to make it “Gallegos” with the double-L being pronounced as “ya.”

Let’s explore the music of the Iberian Peninsula during Alfonso’s time with music of the Jewish and Muslim peoples. First, we turn to the music of Jewish People of the region known as the Sephardim, who populated Spain, North Africa, Turkey, differing from the Ashkenazi Jewish of Eastern Europe. King Alfonso welcomed Christians, Jewish, and Muslims musician into his Court. He respected Muslims, the keepers of classical knowledge and for their sophisticated, cultured and their technological advances. They were poets, artists, artisans, mathematicians, merchants, and ship builders. the Jewish were known as astronomers, writers, economists, scholars, and architects. You’re listening to Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, a musical biography of 13th Century monarch, Alfonso the Wise. Be sure to check out my blog, peopleandcultures.blog for a transcript of this presentation and pictures of the many instruments played in these musical pieces.

King Alfonso employed artists to create two and three-dimensional works of art to correspond to the poems and songs, which would have made the Learned King an early pioneer in multi-media. Now, here we are putting it all in digital form! Scholars say the works of art, the songs and the poems were Alfonso’s way of teaching morality to the subjects of his kingdom on many levels. While those in his court were, themselves, learned and well-educated people, there were many in his kingdom who, perhaps, could not read or write. Hence the need for the lessons in more than written forms.

As we think of the language of Galician-Portuguese morphing into Castilian, and many now call the language “Spanish” coming from Spain, originally. During the expulsion of Jewish and Muslims in 1492, we can see some of the suffixes that may be telling of their origins. Christian suffixes were –ez, -es, and –os. When colonizing other lands, ironsmiths were quite important. Think of the many people you know with the surname of “Smith.” Hierro means iron in Castilian. The surname Hernandez denotes the Christian ironsmiths, and the surname Herrera were the Sephardic Jewish ironsmiths, and the Gallegos hailed from Galicia. We don’t think that the double-l was pronounced with the “y” sound at the time. In case you’re wondering about Galician-Portuguese, the language that is now known as Castilian, here’s a short phonics lesson, “Cs” and “Zs” were pronounced with a “TH” sound or a lisp. Most of those pronunciations hold true today in the Iberian Peninsula. When Castilian came to the Americas beginning in1492, the thousands of Indigenous languages were erased, in most cases, as each of those countries were colonized by Columbus and those who followed him from Spain, a European Country. Spain made it to what is now New Mexico about 25 years before the Plymouth rock landing. Spain continued south and the English settlers moved west, illustrating why we speak English in the United States and much of Canada.

Thanks to the authors who continue to educate me. My references come from the writings of Dr. J.K. Knauss. In addition, I refer to the research of Maestro Jordi Savall, and Maestro Eduardo Paniagua. , John Esten Keller, Robert I. Burn, Editor of “The Emperor of Culture” and from Oxford Univesity’s CSM database.

Thank you for reading my blog. Be sure to listen to this radio program on High Plains Public Radio, December 24, at 2:00 p.m. Central Standard Time. (hppr.org)